Scoring time

The before, during and after of goal timing

Categorising the pattern of goal scoring across game time is one of the more fundamental analyses in team sports. For hockey, we see it done rather coarsely by game quarter in the FIH data and ProLeague pre-match summaries but other sports do it in more detail (in part because of betting) and there are some interesting analytic approaches to modelling the patterns of goal timing. Whether there are any outcomes from these patterns that might hold relevance to actual game play, to adding to our knowledge as players or coaches requires that we have at least a little look to see what might be going on.

The simple questions to ask are, is there any particular pattern in goal timing - are most goals scored early in a game, towards the end, or are they distributed relatively evenly across the 60 minutes of international hockey? And does goal type make a difference - do players score penalty corners in a temporal pattern out of synch with when field goals are put away?

As ever we first have to check if the men and the women do things differently before we can talk about ‘hockey’ more generally. We know they do for some areas (number of goals for example, personal penalties) but that doesn’t mean that everything the two disciplines do is at variance with each other.

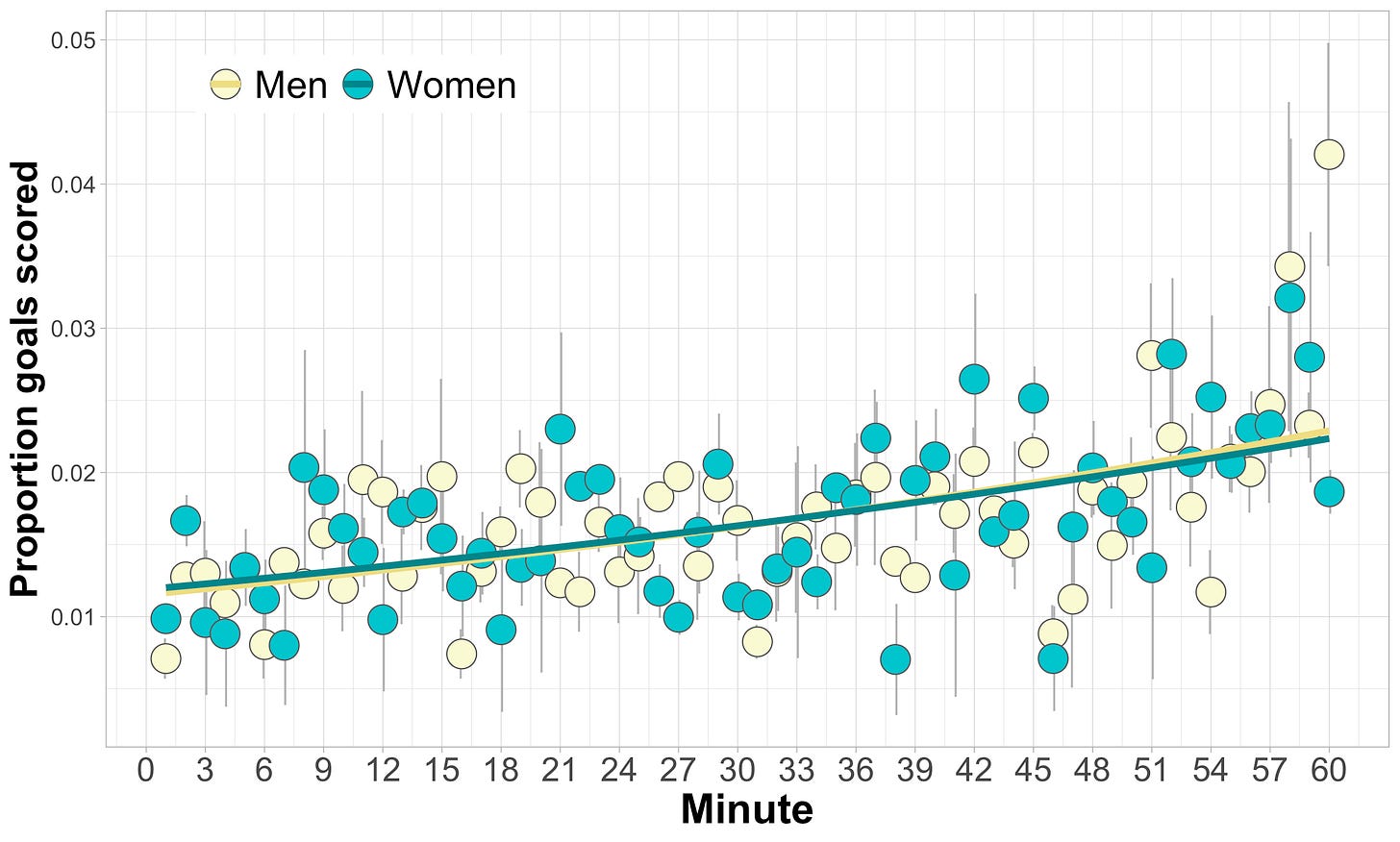

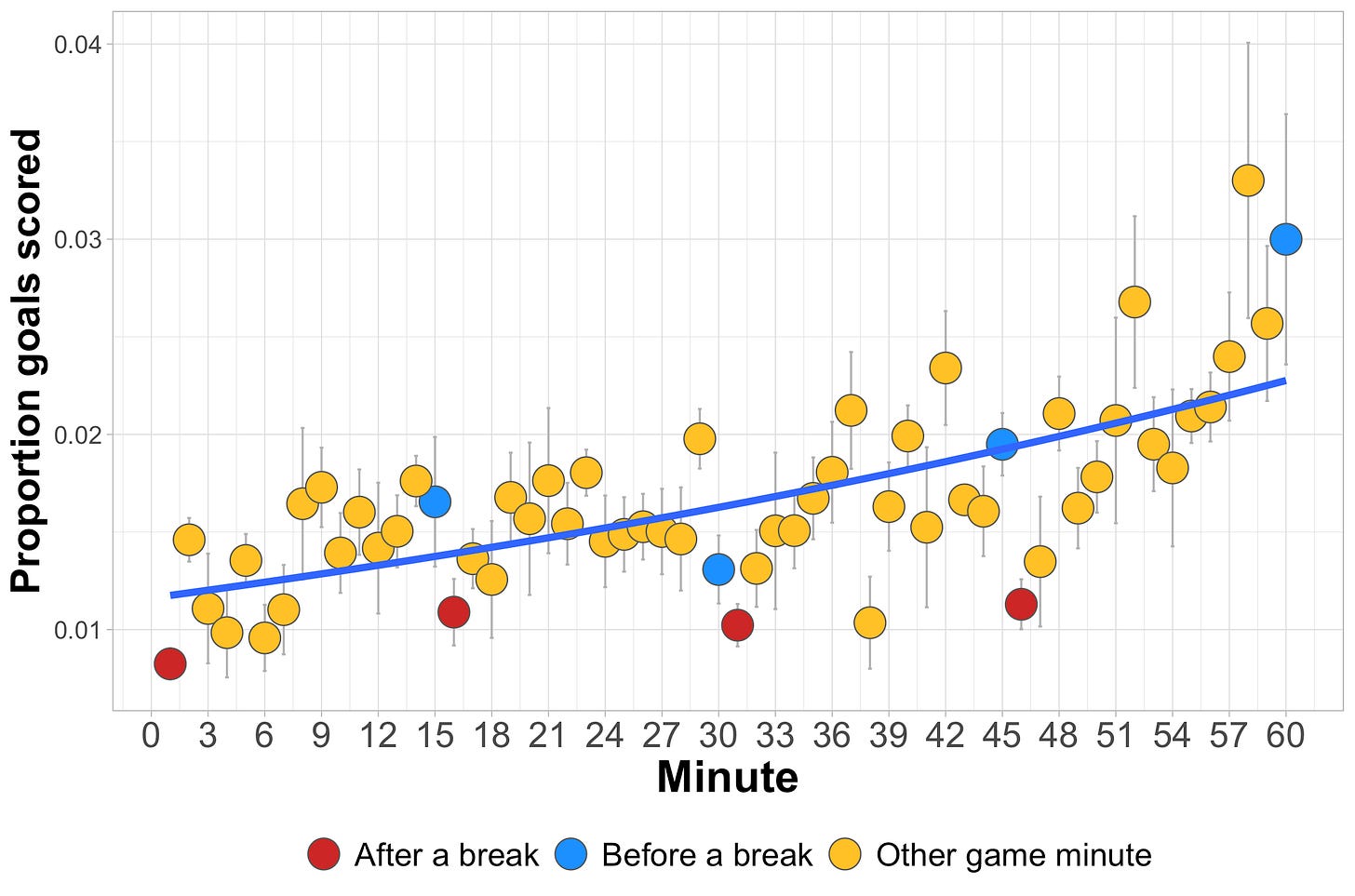

To start then we can simply plot the average proportion of goals scored per minute and develop a model that captures the pattern across time.

You can see that there is an upward trend across game minutes, the proportion of goals scored increases as the game progresses (a significant increase: p < 0.001) but there is absolutely no difference in the pattern between the men and the women (p = 0.4). Indeed the two model curves sit pretty much on top of each other. Remember, this is not a description of how many goals are scored (the absolute numbers don’t matter here) just when they are scored during a match.

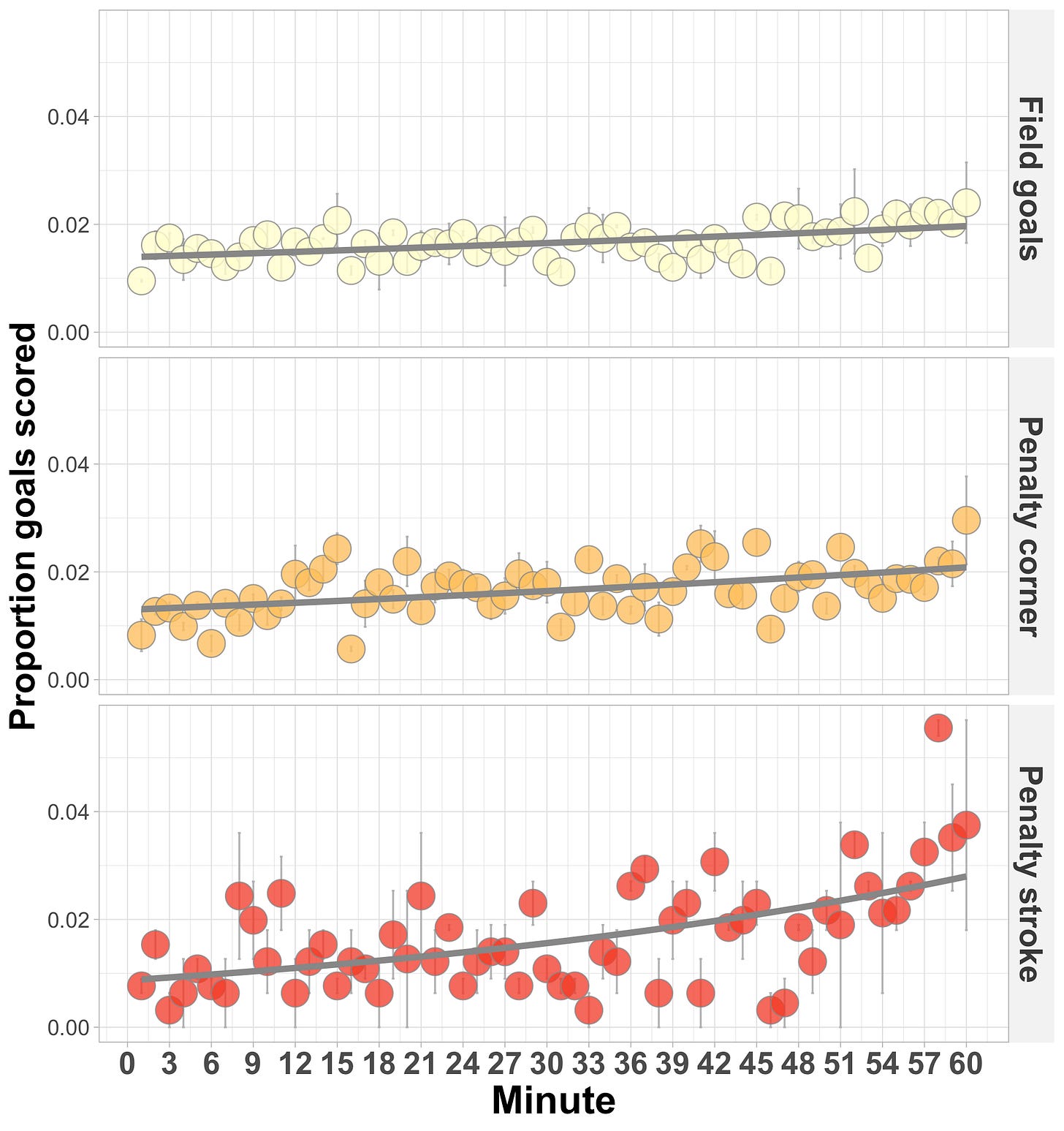

The other question asked whether the type of goals scored differed in their timing.

They don’t. Particularly for field goals and penalty corner goals, which, like the comparisons between the women and men above, are pretty much indistinguishable (p = 0.94). The timing of penalty stroke goals is not different either even though the proportion of goals scored does accelerate more as the game progresses (p = 0.97). This is likely because the variation is larger (smaller sample size - compare the error bars between the three panels). So, though it might appear that a higher proportion of penalty stroke goals are scored towards the end of the game, the difference doesn’t statistically separate them from the other two scoring methods.

Apart from the probability of a goal being scored increasing as the game progresses (the odds of seeing a goal goes up about 1% for every extra game minute) there is not a lot to differentiate between categories, the men and the women score in the same pattern across game time as does the type of goal scored.

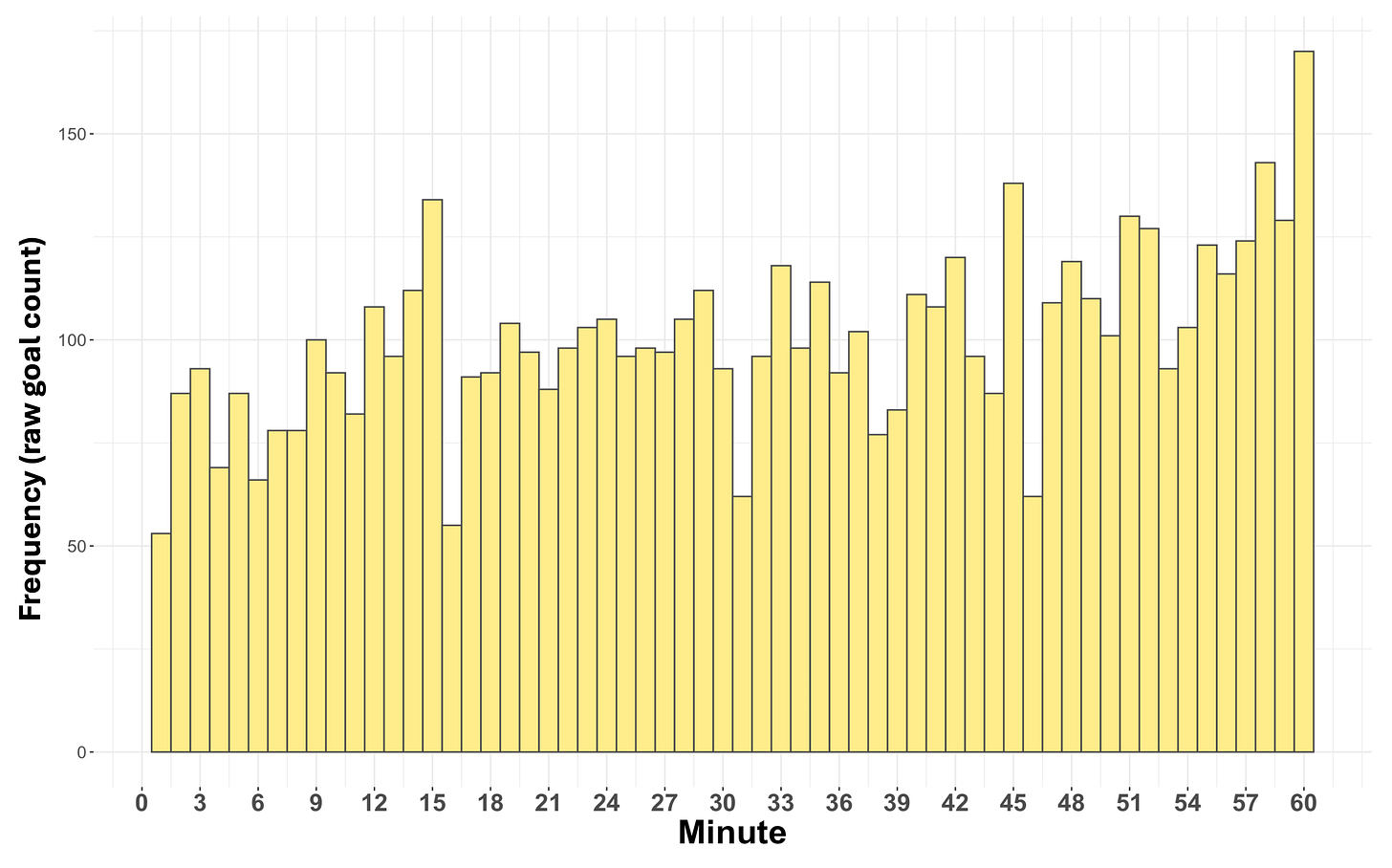

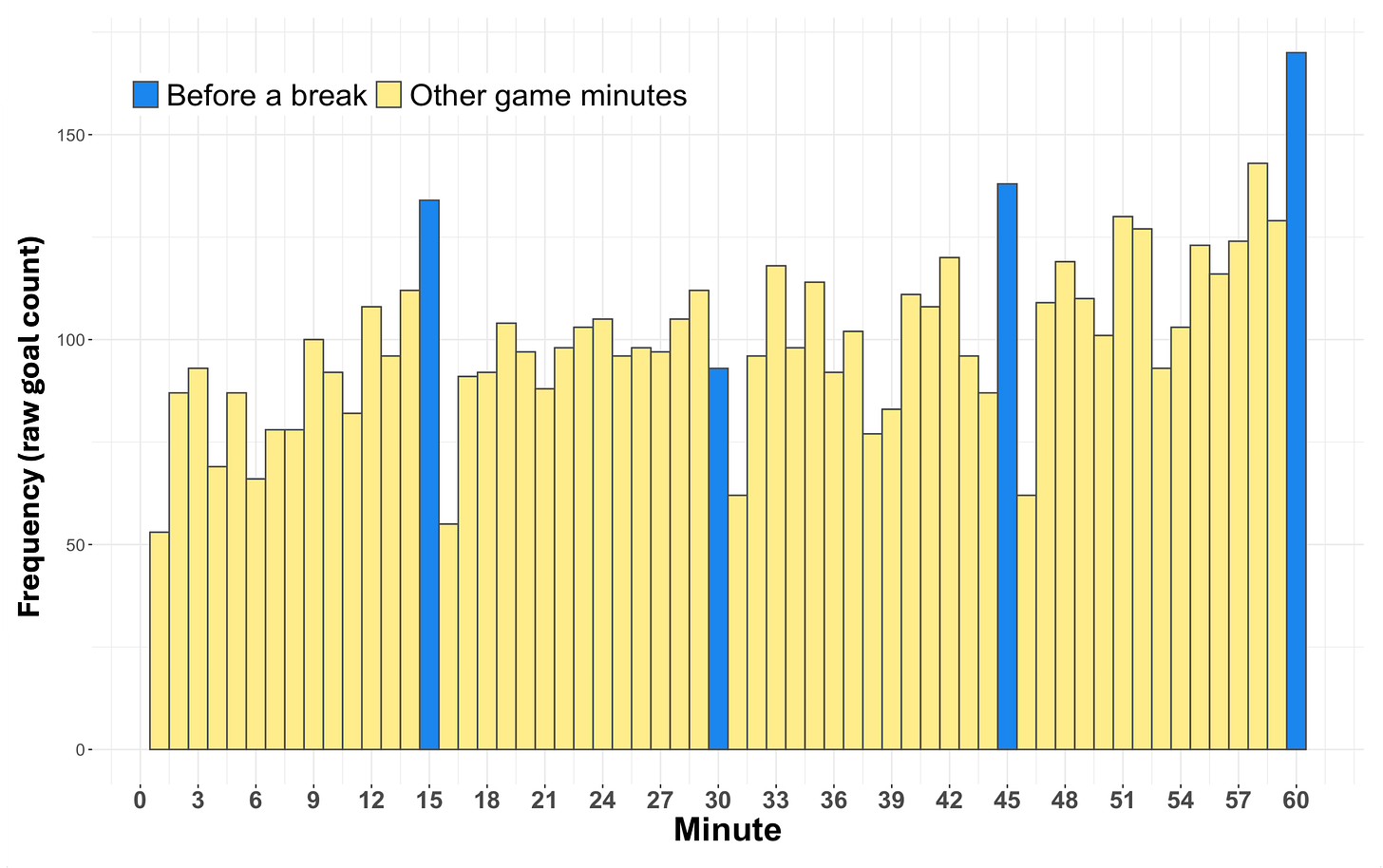

But I have jumped to the chase a little here. What Figures 1 and 2 show are the visual summaries of analyses already completed. What we tend to do first is to summarise and visualise the data to get a feel for any patterns that might appear. Summarise in a frequency histogram for example.

Naturally, there is always variation in data so the ups and downs in the columns here are not surprising. And we have to be careful at guessing patterns we think we might see - our brains are good at imposing explanations that aren’t really there. But still, there may be relevant differences that jump out from this initial data exploration.

I’m sure you have already noticed some peculiarities but let’s highlight a particular pattern that does seem to catch our attention - well mine at least.

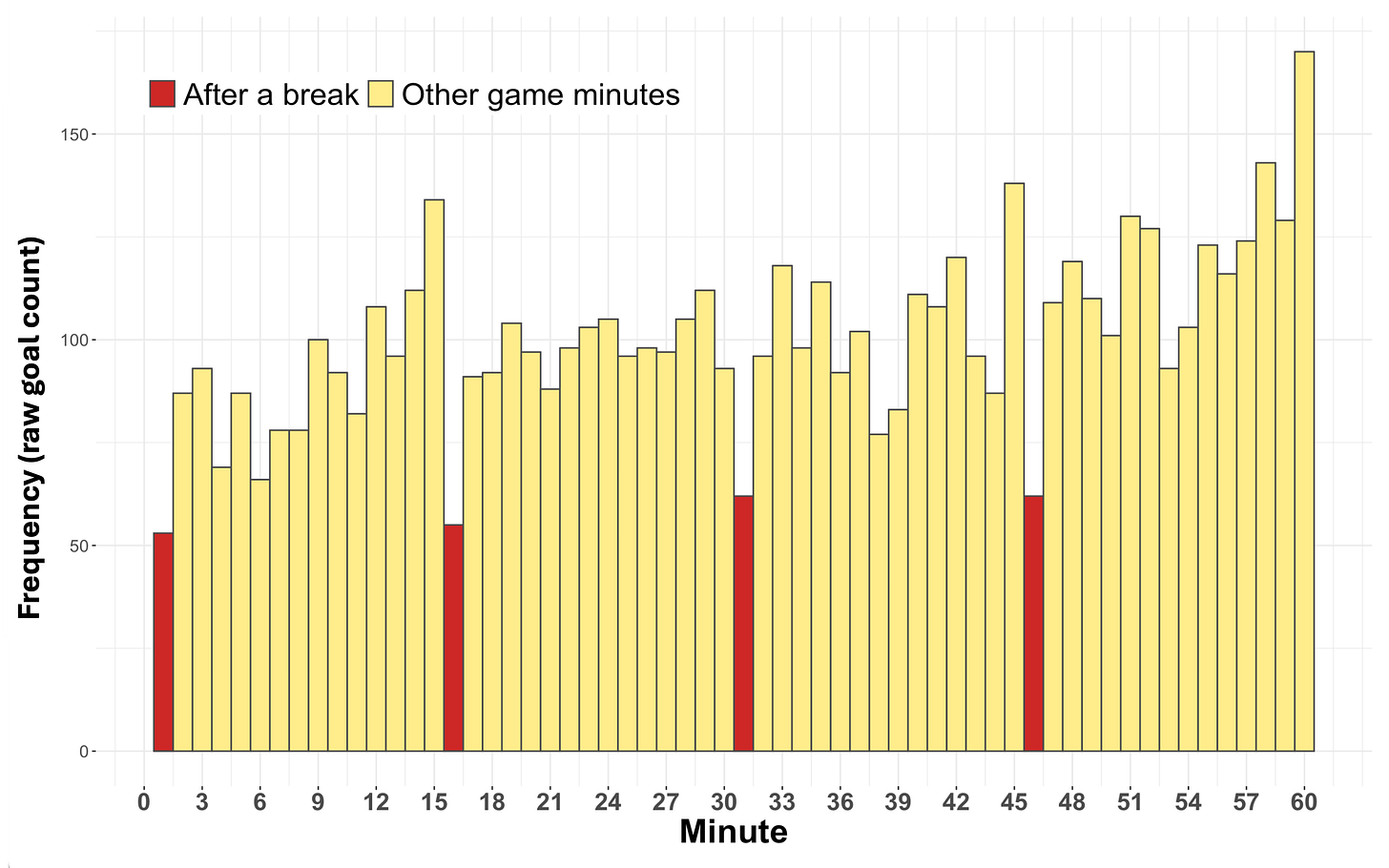

The bars highlighted in red fall in the 1st, 16th, 31st and 46th minutes. They are of course the first minute after a break in the game (if we are allowed to call minute one a break) and seem consistently lower to all other game minutes.

Highlighting these four game minutes brings the pattern clearly to attention but one might also look at this.

The 15th, 30th, 45th and 60th minutes, the minutes immediately preceding a game break. The 30th minute doesn’t seem to line up, but there is a hint, not as strong as the after break minutes, that something different might be going on here too.

They are worth analysing further. If we make three categories and pool all the minutes ‘before a break’ into one, all the minutes ‘after a break’ into a second, and then pool all ‘other game minutes’ into a third, we can look to see if the perceived differences are real1.

And they are. The probability of scoring shows a steady increase as the game progresses (Figure 1) for all goals types (Figure 2) yet within this overall pattern are significant variations at the time categories we’ve identified. The odds of scoring a goal in the other game minutes category is 68% higher than in the after a break category (p < 0.001) but 21% lower than the before a break category (also p < 0.001). Is there an explanation for this pattern, something that coaches might want to pay attention to, or at least keep in the back of their minds?

Well, one rather banal interpretation is that these patterns may be an artefact. Minutes before a break have goals added to them because they can’t be carried over to minutes after a break as happens in all other game minutes. And in contrast minutes after a break lose goals because they are not carried over from the previous minute. An example. A penalty corner is given 58 seconds into the 21st minute of the game. By the time the corner has been executed and scored it is now the 22nd minute of the game - the goal was scored in minute 22. This can’t happen in the minutes before a break. A goal scored in minute 15 and 4 seconds is still a goal in the fifteenth minute but it arguably takes a goal away from the sixteenth minute.

That seems a reasonable explanation for the discrepancies we see in goal scoring and it is testable because the FIH annotate goals scored in ‘extra’ time with a ‘+’ suffix: 15+, 30+, 45+ and of course 60+2. We can redo the analysis and add all the ‘+’ goals (currently assigned to the minute before a break) to the minute after a break as happens for all other game minutes3. Doing this we find the pattern changes.

In Figure 6 the Men’s and Women’s have been combined and the three time categories highlighted. Goals scored after a break are still scored at a lesser rate than other game minutes (p = 0.001) but the effect has been reduced slightly: odds of scoring in other game minutes are 54% higher than after a break compared to the 68% it was previously. What changes more are that the odds of scoring a goal in the minute before a break. They are still higher than the other game minutes but only by 12%, down from 21% (see above), and this is now not different to those other game minutes (p = 0.061).

Scoring rate gradually increase as the game progresses and there is no overall difference in this pattern either between the men’s and women’s game or between the type of goal that is scored.

Perhaps the slight goal drought after a break might simply reflect the psychological re-gearing players go through as they pick the orange pith from between their teeth4 and wonder what the hell their coach was going on about. In addition, the team without the ball does start in defensive solidity with all their players in their own half, a little harder to break down maybe until the game has opened up again. It’s tempting to think of strategies to exploit this goal scoring lull but the data does comes from international hockey where one might expect that fast, post-break starts would all be part of the recipe of the top teams. The fact that post-break minutes have lower goal scoring odds even when taking into account the ‘+’ goals from before the break, suggests there may be something intrinsically difficult about scoring in the first minute of each quarter.

The goals scored before a break lie in a slight existential realm. Practically speaking, there is an uptick, so something to be aware of but this does not appear to be intrinsic to the way the game is played but rather in the way the game is administered. There is one large outlier that can’t be explained as a result of extra time goals however. In the men’s game the probability of scoring in the 60th minute jumps to a wapping 4.2% (see the Men’s value at 60 minutes in Figure 1) and this isn’t mirrored in the women’s game. Some of this is due to extra time penalty corner goals but the effect is still there when these are removed (Figure 6) and there is still the lack of increase in the women’s game that has to be explained. In football a similar effect has been ascribed to teams taking more risks when chasing a result and either reaping the reward or being punished for doing so. So perhaps that is an explanation for hockey too. But why only for the men? An explanation is a little hard to parse.

No big surprises in the overall results then but some interesting quirks around game breaks. And as an analysis of the general patterns in hockey an important one to tick off. The data collected for this also lends itself to some connected questions which I’ll publish as I continue to develop models for other areas of the game.

For completeness I did randomly select minutes during each quarter and compare them to the rest of the data and also deliberately cherry-picked other low and high scoring minutes outside the before and after categories to see if I could find a significant effect. There wasn’t one. The before and after do seem to be real effects whatever the driving factors behind them might be.

All of these ‘+’ goals are of course penalty corner goals. There is no warping of the space time continuum that allows scoring of field goals after the hooter goes, they still have to cross the goal line in regulation time.

This doesn’t apply to minute 1 of course as there are no 0+ goals. Nor does it apply to minute 60. The 60+ goals are simply deleted from this renewed analysis.

No? Orange segments at half time, jumpers for goal posts? Just me then.

So.... when you stated in the beginning...

"The simple questions to ask are, is there any particular pattern in goal timing - are most goals scored early in a game, towards the end, or are they distributed relatively evenly across the 60 minutes of international hockey? And does goal type make a difference - do players score penalty corners in a temporal pattern out of synch with when field goals are put away?"

... the answers are:

1. Yes a slightly upward trend towards the end of the game.

2. No.

Correct?

And no real benefit for a coach or a team to know about it and apply a tactical change to get some benefit from this knowledge?