Scoring the first goal

Is it really that important?

Introduction

A little while back I was looking for some example analyses on how playing at home or away influenced the outcome of games. The home-away comparison has never been done for hockey though it is a much studied area in other sports. My little jaunt amongst the academic papers and amateur analyst’s output on this topic turned up an unrelated and, what to me was, a very surprising detail. In football the teams that scores first win 65% of their games. What’s more scoring first ensures that you don’t lose 93% of your games.

Naturally, I wondered if this was the case in hockey. To find out I did a little analysis using data from the top three Dutch domestic leagues1. Since that analysis was club hockey I thought it worth checking whether the results I’d found were relevant for an international tournament. And as the Olympics have just been round on its four year orbit once again what better way of comparing club results with something from the top international tournament.

Is scoring first important in hockey?

Yes, it certainly seems to be. On the men’s side, teams that scored first during the Olympics won 63% (± 0.08) of their games, a similar rate of success to the football statistic that originally piqued my interest. And for the women the percentage is even higher: 71% (± 0.07). In both cases teams that score first don’t lose 82 and 87% of their games for the men and women respectively. That’s slightly lower than football and may reflect the fewer drawn games in hockey. For the rest of the article I’m just going to talk about how scoring first influences winning and leave aside the ‘not losing’ side of things.

A difference between the men and the women?

The slight difference between the probability of winning in the men’s and the women’s game is worth checking.

There is a slight interaction. The men don’t win quite as many games after scoring first as the women and they win slightly more than the women if they don’t score first. But the important point here is that it is a very slight difference and certainly not significant. Which is good because it means we can now pool the men’s and women’s data into one Olympic ‘hockey’ dataset - something we couldn’t do if, for example, it was the number of goals or personal penalties.

What other factors influence winning?

The million dollar question. A lot of time has been spent analysing what makes for a winning team in other sports so pundits can go down to the bookies and lose their money2. In the context of this article the focus is really on the importance of scoring first. So let’s keep it simple, use that variable and throw a few others into the model and see what it keeps as an important predictor of winning.

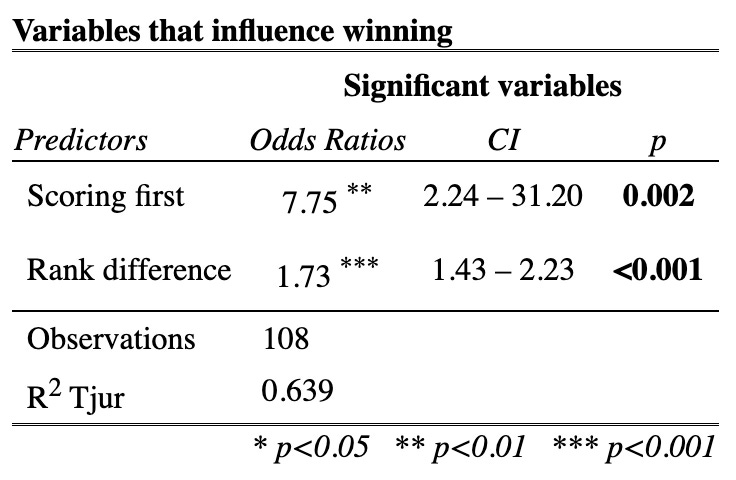

Interestingly, the only variable it does keep from the handful included was the rank difference between the teams. In fact it is a slightly better predictor of game outcome than scoring first explaining around 34% of the variation in winning compared to 24% explained by scoring first3. This is not really surprising. If the number one ranked team (say the Netherlands in the women’s game) plays the bottom ranked team (France from the last Olympics) most of us would make a confident guess at the winner. But scoring first has an important part to play too.

The relative importance of rank and scoring first

In Figure 3 the probability of winning (the vertical y axis) is compared to the difference in rank between each team across all matches (the horizontal x axis). And both are separated into teams that did not score first (top panel - ‘No’) and those that did score first (bottom panel - ‘Yes’).

In the ‘No’ panel teams with a high rank difference to their opponents generally win all of their games. Rank differences of 10 and 11 places are missing because there were no games in which they conceded the first goal. And a rank difference of 7 only has one example (Netherlands versus Great Britain in the men’s tournament where the Dutch scored first and GB came back to draw). But rank differences of 1-5 are more common and these teams won only half or less of their games if they didn’t score first even though, on paper, they were better than their opponents. Negative rankings, i.e. teams pitched against higher ranked opponents, hardly register a win at all if they don’t score first.

The second panel (‘Yes’) shows how scoring first can make a difference. Not only does having a high rank difference lead to wins after scoring first, but scoring first also helps teams win that only have small positive rank differences to their opponents. Teams ranked lower than their opponents are still likely to lose but they at least have more of a chance if they score first than if they don’t.

Makings some simple predictions

Figure 3 is taken from the actual tournament data and so is specific to the 2024 Olympics. But the modelling process allows us to generalise from that data. Below, in Table 1 are predictions for the probability of winning when only the rank difference between the teams is taken into account.

The teams are an arbitrary A, B and C with nominal rank differences to their opponents of 5, 1 and -5. It’s all fairly straightforward, the higher the difference in rank, the higher the probability of winning. Note that the team that has a slight positive rank difference (Team B) aren’t predicted to win more than half their games because the modelling counts draws as not winning. Harsh, but there you go.

The impact of scoring first can be seen if we use the complete model from Table 1.

Scoring first clearly adjusts the win probability predictions. For a team five ranking places above their opponent they are still likely to win under both scenarios but, if they don’t score first they may have to work a bit harder, the probability of winning is 30% lower than if they do score first. As discussed above in relation to Figure 3 the largest impact comes when the rank difference is small. With a ranking one place above their opponents Team B have an excellent chance of winning if they score first but woe betide if they let their opponents sneak that first goal - there’s a fifty percent swing in the probability. And then teams that concede a number of ranking places to their opponents will struggle but at least scoring first provides a glimmer of hope that they can pull off an upset.

Scoring first does matter then, it can temper game outcome probabilities when differences in rank are high and hugely influence game outcome when differences are small.

Simple arithmetic?

Why does scoring first have such an impact? Much has simply to do with hockey being a low scoring game. The last four major women’s tournaments (ProLeague, EuroHockey, World Cup, these Olympics) have seen an average of between three and four goals per game. So consider a match in which a maximum of three goals will be scored by the time the final whistle goes. Each team (ignoring differences in rank) can win the game in four different ways (1-0, 2-0, 2-1, or 3-0) and draw in two (0-0 and 1-1). But if your team concedes the first goal they can now only draw 1-1 or win 2-1. Conceding that first goal has seen the number of ways you can win go from four to just one. Your opponents on the other hand, can still win the game in four different ways.

The above would suggest that scoring first should have less of an influence in games with a high goal count. Maybe this can be seen in the men’s game where the average is around 1.5 goals a game higher than the women’s. Unfortunately there is just not enough data from the Olympics to really test this (but see footnote 4 below). The idea is taken to its obvious conclusion in high scoring games like basketball where scoring first matters not a whit to the final outcome.

What do we tell our teams?

I don’t know about other coaches but I guess it’s common that we urge our teams to start at a high tempo, to wrest the initiative from our opponents, to impose our game on them. I wonder though, how often we exhort our players to go out and score the first goal. Perhaps we do, perhaps it is implicit in the pre-match verbiage, something unspoken that all the players understand.

But I also wonder whether any of us specifically set-up a team to get that first goal. To throw whatever caution may be the chatracteristic commonplace approach, to the wind, design a tactical strategy and then go, bat-out-of-hell for a goal.

This is a double edged sword of course. If we tell the players how important that first goal might be, particularly when your team is closely matched to the weekend’s opponents, the corollary is that conceding the first goal can be psychologically problematic. Can your team buck the subsequent low chance of winning and come back to take the game?

The women’s team I coach are four games into our twenty-two game season and it has become apparent to all the coaches that this year the competition will be extremely close. Whatever the league positions say, the reality is that there is not more than a ranking point difference or two between any of the twelve teams. The analysis says that the probability of winning will be hugely influenced by who scores first (and the league results so far agree). So, go gung-ho for that first goal? Or not?

What would you do?

In that analysis 69% of the teams that scored first won their games in the top three of the women’s Dutch leagues and just checking the state of the current Hoofdklasse competition after three rounds shows 71% winning if they score first. A very tight distribution suggesting that this is a consistent predictor of game outcomes in hockey

We could do this. Build a model to predict who will win a game of hockey (a more complicated one that in the main text - see Footnote 2 below). It would take some effort to collect the data but the model itself isn’t difficult to develop. But, you know, who on earth wants to make money from betting on hockey!?

The point of interest is whether the game was won or not and that is a binary outcome that lends itself to a general linear model (glm) with binomial errors. We include the ‘Scored first’ and ‘Rank difference’ as key variables to help predict who will win along with a few others (whether it was a pool game or knockout (Game type) or men’s or women’s game (‘Discipline”) for example). In theory, there are a lot of reasons (variables we could include) why a team might win a game but this is not an exhaustive model and we are just looking to see how much of the variation (‘deviance’ in glm speak - how good a predictor the variable is) can be explained by scoring first.