Introduction

The recent resumption of the ProLeague reminded me that I wanted to re-examine an analysis I had done a little over two years ago and update the dataset with more recent tournaments. The data is to do with the number and type of cards umpires give out. I was collecting this data for a connected analysis (whether personal penalties influence game outcome) but some of the results arising from comparing umpires and the way umpires award cards became an interesting analysis topic in its own right.

A very brief summary of personal penalties in international hockey would be that over the last six years 6.7 minutes of penalties are awarded, on average, per game - somewhere around three greens, or a green and a yellow five minute card.

Now note, I am using a penalty minutes as a metric. This value is a useful way of concatenating the different cards into one measure. The minute value of the individual cards shown during a game are simply added up to give the overall personal penalty burden for that game or for each umpire. This means we don’t have to talk about the number of cards (which loses some precision as card values are obviously different) nor have to tediously analyse each card type separately. Hence, two greens and one yellow five minute card can be summarised as nine penalty minutes. Generally through this article I will be talking about penalty minutes to describe the quantity of personal penalties umpires are giving and step back into the specific cards when doing so adds some information.

Differences between men’s and women’s hockey

The overall value of 6.7 minutes per game is good to know. It might provide a baseline for looking at whether seven-ish minutes of unbalanced play (i.e. one team has fewer players) is enough to consistently affect match outcome. But, the trouble with this summary is that it assumes the men’s and women’s game receive personal penalties at the same rate. That’s quite an assumption given that we already know some aspects of the game differ (for example goal scoring) between the two disciplines. So it is important to check that the number of penalty minutes awarded is similar for both1.

It’s not. Overall the men’s game receive about two penalty minutes a game more than the women’s game and this is a significant difference (IRR = 0.77 (95% CI = 0.69-0.88), P < 0.001). Here we can dive back into the cards themselves to see where this difference arises.

The number of green cards shown, though apparently similar, is different (P = 0.009: a consequence of a nice large sample size) but in a match context this difference is relatively small (about a 15 seconds extra time in the sin bin). The main difference is the men escalating to yellow five and ten minute cards more frequently than the women (for example yellow 5 minute cards add nearly an extra minute of penalties and yellow 10 minute cards a further 30 seconds per men’s game).

Mixed umpiring

Now we come to the nub of what I thought was interesting point about the umpires and their cards. For the 2020-21 ProLeague, female umpires who had previously only umpired in the women’s game were allowed to umpire men’s hockey. And vice versa - male umpires were allowed to cross over and umpire in the women’s game. Now matches could be officiated by all women, all male, or mixed pairings in both disciplines2. And that of course must be good. But the result shown in Figure 1 prompts a quite fundamental question.

Both the men’s and women’s game play over the same period of time, on the same pitch and overall, under the same rules. Yet not only does game play differ but so too does the umpires’ response (see Figure 1 and 2 above). Given this, how would the difference in personal penalties given by male and female umpires in the men’s and women’s game affect, if at all, an umpire’s award of personal penalties when they cross disciplines?

What one might expect is that the umpires will adjust to the person penalty needs of each discipline. Hence male umpires when appointed to a women’s game will give fewer penalties than they are used to, and female umpires appointed to a men’s game will bump up the number of cards they give. A nice, simple theoretical framework to test.

Do male and female umpires award personal penalties at the same rate?

To examine this we need to look at the penalty minutes given by individual umpires (rather than at the game level as in Figure 1 and 2) and divide them up into four categories, male and female umpires in their tradition disciplines of the men’s and women’s game. And then male and female umpires in mixed pairs, umpiring in the two game disciplines3. For just the traditional combinations the answer looks like this.

The summary is exactly a repeat of what we have seen already (see Figure 1). Individually, male umpires officiating in their traditional men’s tournament environment give about four penalty minutes each per game (mean = 4.11), not different to the overall result from Figure 1. Similarly female umpires in the women’s game give about two and a half penalty minutes per game (mean = 2.49) and so around five penalty minutes per game. So all good, all nice and sensible and the two groups maintain their difference between each other (IRR = 1.65 (95% CI = 1.34-2.04), P < 0.001).

What happens if we look at the rate when male umpires officiate in the women’s game.

Male umpires reduce the level of personal penalties they award when umpiring with a female umpire in the women’s game. The average number of penalty minutes male umpires give (mean = 2.89) is still a little higher than female umpires but not significantly so (IRR = 1.16 (95% CI 0.83 - 1.62), P = 0.7). Yet it is significantly lower than the penalties they give when officiating the men (IRR = 0.7 (95% CI 0.51 - 0.97), P = 0.025).

And the female umpires when they move to the men’s game?

Different again. Female umpires officiating in the mens game award personal penalties at the same rate they do in their traditional, women’s game environment (mean = 2.39), significantly fewer than male umpires in the men’s game: IRR = 1.72 (95% CI 1.22 - 2.42), P < 0.001, but not different to the other two combinations (P = 0.7 or higher).

What is the difference between umpires in same gender and mixed pairs?

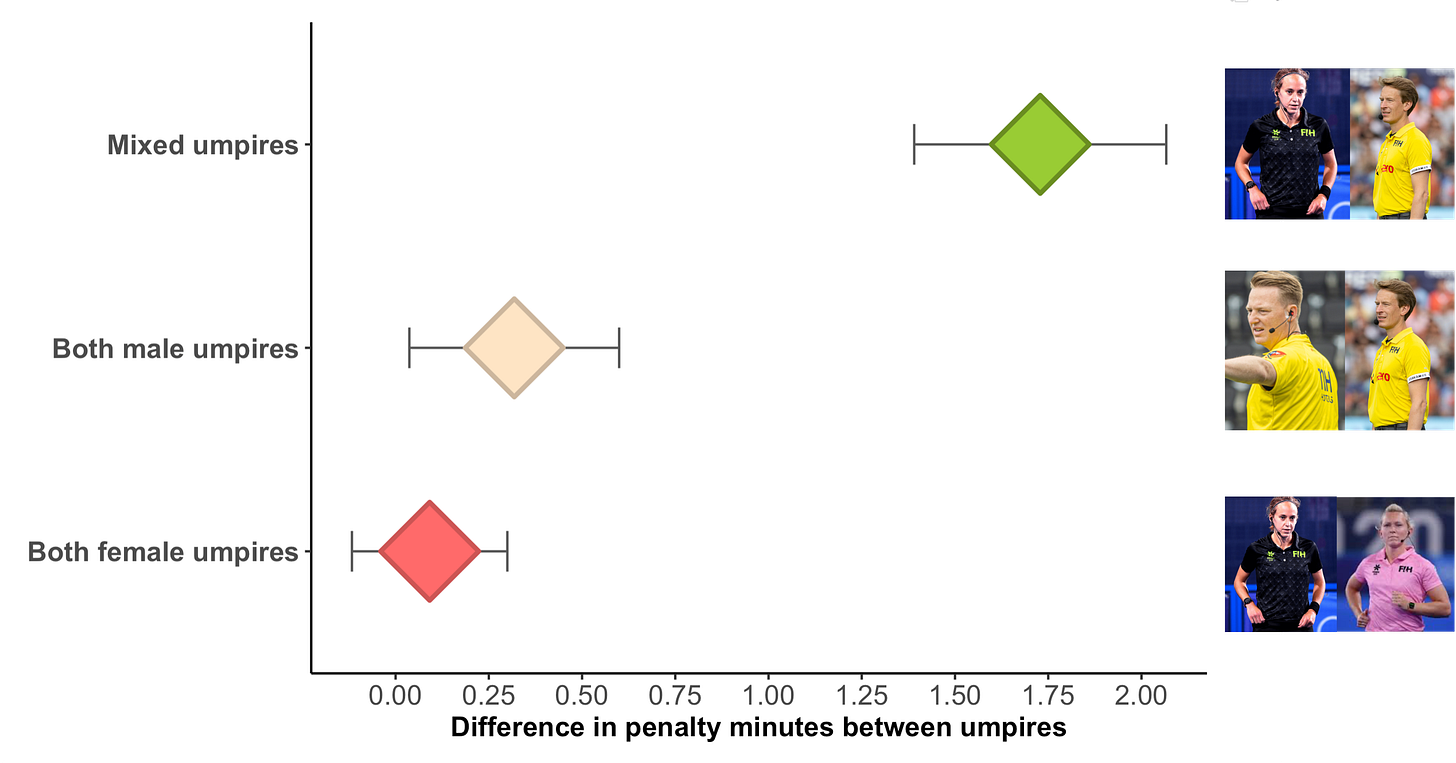

Before we start trying to interpret these results we need to open the data up a little more. Figures 3a-c focus on just the umpire, the individual umpire in each game and the penalties they award. What would also be good to know is how well balanced the awarding of personal penalties are between the different umpire combinations (both male, both female, or a mixed male - female pairing). We would expect, given sufficient games to analyse, no real difference in the number of personal penalties two umpires award. Game to game there will be variation of course, it would be silly to expect umpires to give out the same number of cards as their colleagues every game. But if we average out the difference in penalty minutes between the two umpires officiating a match over a decent number of games it should be close to zero. Is that true?

No, at least not for every pair combination. For same gender pairings it is true that over a reasonable number of games the difference in penalty minutes given out by the two umpires on the pitch is not different compared to a theoretical baseline (mean difference = 0, sd = 5), nor were they different to each other (P = 0.88 or higher for all comparisons between baseline and same sex umpire pairs). However, when a male umpire is paired with a female umpire there is a significant and consistent difference (P = 0.003 or lower across all comparisons). Male umpires give out nearly two penalty minutes more per game than their female colleague when they share umpiring duty, a pattern that does not occur in same gender umpire pairings.

We can do one more bit of digging. Does it matter which of the two game environments these mixed pairings officiate?

Yes, to a certain extent it does. When male umpires officiate with a female umpire in the women’s game they tend to give out more penalties than their partner (an average of 0.81 extra penalty minutes per game) but this is not different to the baseline (P = 0.7). However, when male umpires officiate with a female colleague in the men’s game there is a clear difference (P = 0.001), male umpires again give significantly more penalty minutes (2.62 extra minutes per game) than their female colleagues when they are both officiating men’s hockey.

We can put the two mixed pair environments together and summarise the proportion of penalties each umpire is responsible for in each game discipline.

The dotted line is what we would expect - the number of personal penalties each umpire gives in the mixed pair should be balanced and hence makes up about half of the personal penalties given during the game. But Figure 6 emphasises this is not the case particularly when there is a mixed pairing in men’s hockey. Here getting towards 70% of the personal penalties are given out by the male side of the pair - hardly a balanced partnership. In the women’s game the effect is more muted and the difference not significant, but the difference does appear relatively consistent. Nor does it seem the pattern is settling to equilibrium over the years of experience the umpires are gaining. The current ProLeague tournament indicates male umpires are still giving penalties out at a higher rate per game in both game disciplines - 2.2 minutes more in the men’s game and 1.6 minutes - when umpiring with a female partner.

Summary

The data and results from the analyses indicate that there are clear and consistent differences between umpires officiating in international hockey. These is particularly apparent in the men’s game where male umpires give more personal penalties than their female partners. By contrast, female umpires consistently award fewer personal penalties than their male colleagues.

As mentioned above, one might expect that the awarding of personal penalties is driven by player behaviour. Accordingly, the men’s game, arguably, has a higher frequency or intensity of wrongdoing, perhaps because player behaviour is more robust, more physical, the dissent more pointed, in comparison to the women’s game. The level of personal penalties might reflect this and the decrease in cards male umpires award when they move to the women’s game is a consequence of a lower offending rate in that discipline. Female umpires partially support this explanation too. When they officiate in the women’s game, they also give fewer cards. But the tricky bit is that unlike their male colleagues, they do not adapt to a higher rate of personal penalties that are apparently needed in the men’s game. How to explain this?

We could see this as some sort of reciprocal transplant experiment4 in which male umpires have adapted quickly to the new environment of the women’s game, perhaps because demands are less and so reducing the number of personal penalties they have to award is relatively easy. Female umpires on the other hand, have a more difficult ladder to climb. Adaptation takes longer, the preconceptions they carry from the women’s game more difficult to change when the demands made on them by the men’s game are that much higher. As a consequence, female umpires stick to what they know, award personal penalties at the rate they are used to in their traditional environment and eschew the apparent need for an increase in personal penalties.

It’s a thought I suppose. But not one I buy. For a start, this would ignore the fact that all these umpires have now had five and a half years and a similar number of mixed umpiring tournaments to get used to the other environment. Indeed, that may not even have been necessary since I would imagine most, if not all, umpires already had, and have continued to experience cross-discipline umpiring in lesser international games, like test matches, and certainly in domestic hockey - Dutch domestic leagues have had mixed umpiring “voor altijd”. And as for the physical differences? Can you really see Sarah Wilson, for example, being intimidated by the muscularity of the men’s game? By their testosterone protestations when male players feel wronged? No, neither can I.

An alternative interpretation of these results is that male umpires simply give out too many cards. Female umpires show that, in the men’s game in particular, it’s possible to officiate well5 by consistently giving fewer cards than their male colleagues without compromising game cohesion or control. Male umpires, in this view, may rely too much on cards for control rather than player management and could look to female umpires for an alternative approach and more modulated approach. If this is true then the differences shown focus more on a gender bias in umpire interpretation of player actions and not so much on an explanation driven by supposed differences in player behaviour: both disciplines are, after all, just as committed, physical and, at times, verbally colourful as each other.

To get into this beyond these broad speculations requires more and different data. But what can be said now is that mixed umpire pairings not only show biases in the awarding of personal penalties but also may shine a light on inherent differences in the way male and female umpires view and subsequently officiate international matches. Research in other areas (judicial decisions for example) show similar gender based differences. An interesting point made in one of these studies (and also interestingly made about cognitive biases more generally) is that they are inherent and very hard to eliminate. But, making individuals aware of these biases can ameliorate their effects.

I wonder if the FIH is already highlighting this as part of their umpire training?

I’ve updated the original data set for these subsequent analyses. There are now four ProLeague tournaments that can be used to generate data to test this question: 2020-21, 2021-22, 2022-23 2023-24 and half of the 2024-25 tournament. The Eurohockey 2023 tournament also had mixed umpire pairing and is included. By contrast Eurohockey tournaments 2019-2021, World Cups 2018 and 2022 and the 2020 Olympics (data for the 2024 Olympics is not available) are also included as examples of ‘traditional’ umpiring set ups where male umpires officiated in the men’s tournaments and female umpires in the women’s.

This may be a strictly international hockey phenomenon. At the domestic level men regularly umpire women’s matches and women umpire the men. But, officially at least, the 2020-21 ProLeague tournament was when each umpire group stepped out from its traditional hinterland and shared the bigger stage. Steve Rogers was the first male umpire to officiate a women’s international and Aleisha Neumann the first woman to umpire a men’s international.

It would be interesting to look at all male pairs umpiring in the women’s game and all female pairs umpiring the men. However, the examples are too few, just seven matches where an all female pair umpired men’s hockey and double that for an all male pair umpiring in women’s hockey. Not enough to analyse.

Yes, forgive me and my ecology background but the whole exercise fits well into a reciprocal transplant experimental framework. It is in fact what I thought of when I did the original analysis.

I’m guessing here. I have no insight into whether umpiring coaches at the FIH think that female umpires in the men’s game are umpiring ‘well’ (or vice versa for that matter), but as the practice of mixed umpiring continues I am going to assume that the FIH think everything is hunky-dory. It does raise a question of why there isn’t mixed umpiring in the Olympics or World Cup. Perhaps an expert can chip in and advise.

Simon, there was mixed gender umpiring in Paris for the first time at an Olympics. (I noticed at a game I attended - GB vs USA). But I don’t know how widespread it was.

Interesting article and data.

One thing that came to my mind when seeing fewer cards/minutes being given by female umpires than male umpires in the Men’s game was their umpiring might be similar/consistent to each other, but the player behaviour itself changes depending on who is umpiring.

Purely anecdotal evidence, but from my experience being umpired by both male and female umpires in the Men’s game, I think male players are much less likely to escalate verbal abuse at female umpires…and hence pick up fewer cards for that particular offence.